- Home

- Robert Asprin

For King and Country Page 12

For King and Country Read online

Page 12

"Ancelotis," the priest greeted him solemnly, "because time is of the essence, do you swear before Christ to uphold the laws of Gododdin and protect her from all threats until your nephew is of age to rule in your stead?"

"I swear it," Ancelotis replied, voice hushed with grief.

"Wear the royal torque of the kings of Gododdin then, and pass it on to Gwalchmai when the time is ready."

Ancelotis pulled off the torque he had worn all his adult life, then bent his head, for the priest was shorter than he. Lot Luwddoc's royal torque was far heavier around his neck, with a weight of more than poured and beaten gold. Queen Morgana, grey eyes brilliant with unshed tears, kissed each of his cheeks by turn and it was done. In a moment of brilliance or madness, Stirling wasn't sure which, Ancelotis turned to Morgana's nephew Medraut, who had watched the proceedings with shadowed, hurt eyes and a neck bare of any adornment.

His mother had been executed, leaving him with uncertain status in their carefully measured world. Ancelotis gave the boy his own, princely-rank torque. "I make you the holder of my honor, Medraut. Guard my own torque as you would guard the welfare of your family, and remind me that I am king only to save Gododdin for the sons of Morgana and Lot Luwddoc."

The boy's eyes widened, glowing with the shock of unexpected honor as Ancelotis placed the golden ring around the boy's neck. Morgana, watching from the side, allowed the tears to fall unheeded, as Medraut was transformed from an awkward boy, uncertain of his welcome and place, to a young man with purpose and the respect of his elders.

"I will not fail you, Ancelotis!" the boy swore, gripping Ancelotis' proffered hand and forearm in a tight grip.

The watching councillors of Gododdin, momentarily startled by the move, began to nod as they saw the wisdom of the thing, binding Morgana's nephew—until now an unknown factor in the politics of the north—firmly to the new king.

"Councillors of Gododdin," Ancelotis said quietly, "I thank you for the faith you've placed in my trust. Please take my brother's body home and see to it he is buried with all honors. Nothing but the safety of the realm could tear me away at such a time, but the Saxon threat must be met and countered."

The councillors bowed, murmuring assent and understanding. Then it was done and Ancelotis went striding across the hall, determined to leave as quickly as possible. The sun was just rising above the hills to the east, toward the distant Firth of Forth, when he and Stirling emerged from the Roman fortress of Caer-Iudeu with Artorius on their shared heels. Not that Ancelotis could actually see the sun. Heavy violet smudges of cloud, thick with unshed rain, raced overhead, casting a deep gloom over the fortress walls, the sprawling rooftops of the town below the cliff, and the forested mountains beyond.

Caer-Iudeu was larger than a fort, which generally covered a mere one to four hectares of ground, but was considerably smaller than a twenty-hectare fortress. The wall enclosing it ran along all four sides, studded with wooden watchtowers every few meters. Long, narrow stone barracks followed the classic Roman camp pattern, roofed in overlapping sandstone shingles, heavier and more permanent than clay tiles and the Romans' favorite roofing material for these northern forts. Workshops and granaries were visible, as well, along the neatly ordered streets inside the fortress walls. The fortress was a beautifully maintained symbol of organized military power, one that must have an ongoing, deep psychological impact on the Pictish tribes to the north.

Judging from the position of the sun, the chill in the air, and the canopy of blazing crimson and gold amongst the trees down at the foot of the cliff—many of them already winter-bare—he'd arrived in late autumn, always a raw season in Scotland. The forests were a startling change from the bleak hillsides Stirling was used to seeing from this vantage point, high on the cliff of Stirling Castle—which would not exist for more than a full millennium. He curled his lips slightly at memory of the modern Scotsman's bitter, private joke about his wild, open hillsides, so popular with tourists.

The Scots lived in the wettest desert on the face of the earth, a landscape of low scrub and heather, kept deforested by high populations of sheep and large herds of deer. The sheep and the deer were carefully maintained by the landed nobility—many of them English—for their enjoyment in the kingly sport of hunting. Even native Scots landowners found it lucrative to maintain large deer herds, the better to earn money from enthusiastic tourists who came for the hunting. The dour hills weren't good for much else, really, besides growing timber, and money could be had far more quickly from sportsmen than from a stand of trees that took decades to mature.

Stirling had forgotten that the wilds of Scotland had once worn a thick mantle of virgin forest, filled with eerie shadows, drifting fog, and white-water cataracts roaring down through untamed glens. Early morning sunlight spilled through occasional rents in the clouds, striking the ancient trees with golden fanbursts. The forest had been cleared a good hundred yards from the outer stones of the Roman wall around the town, providing a wide perimeter of open ground across which an attacking army would have to charge, exposing themselves to fire from the defending fortress.

A full hundred horsemen of the Briton cataphracti waited, already mounted on massive animals that must have been the direct ancestors of medieval chargers. They greeted him with a great shout that sent the rooks flapping in alarm from nearby trees. The men were beating the flats of their swords against their shields. Ancelotis returned the salute even as Stirling's first real shock detonated behind their shared eyes. The faces of a startling number of those cavalrymen bore distinctly Oriental features—and the ones who weren't Asiatic still looked Middle Eastern, Iranian, perhaps. They looked for all the world like a band of the Great Khan's hordesmen—or refugees from Darius' Persian army—lifted out of Central Asia by a playful godling and dropped in the hills of Scotland.

He stared at the Asiatic horsemen, trying without much success to figure out where the devil they'd come from. Ancelotis' silent answer struck him with the strength of a thunderclap: Sarmatians! Memory stirred even as the impact of the word detonated. Sarmatian auxiliarymen... Thousands of the wild horsemen, Sarmatians and Alanians from the Hungarian plains to the steppes of Russia and even as far away as Central Asian Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, had joined the Roman legions as auxiliary forces, mainly in the cataphracti—and the cataphracti was Artorius' strongest weapon, giving him a winning edge over Saxon invaders, an edge slated to last for more than fifty years, all told. There must have been thousands of Sarmatians stationed in Roman Britain, along Hadrian's and the Antonine Wall.

Aye, Ancelotis said with a hint of amusement in his thoughts, fifteen thousand Sarmatians in all, the records say, were sent by Rome to patrol the border. A fair number of them decided Britain suited them better than Italy, so they stayed when the legions left a hundred years ago. Stayed and married the Briton girls who'd captured their wild hearts.

Stirling was speechless. Among the best cavalrymen of the ancient world, the Sarmatians had held their own against Scythians, Persians, Germanic tribes, Gauls, Parthians in the deserts of the Middle East, and Carthaginians in Northern Africa. Over the millennium and a half separating Stirling's time from this one, the Sarmatian blood of the men who'd elected to remain in Britain must have been diluted until virtually no trace of Asiatic features remained in the gene pool.

But in a.d. 500, barely a century had passed since the departure of the legions—and a century was not nearly enough time to dilute the bloodlines of several thousand Asiatic warriors. He caught glimpses of battle pennons and shields bearing what must have been Sarmatian symbols, since only those men with Asian features carried them. Most of their spears were topped with bronze dragon heads, to which cloth banners had been tied, fluttering like windsocks, mouths wide open, with tails that ended in streamers flying wild as their Asiatic owners. And the symbols painted on their shields... A sword plunged into a stone was shocking in this context and left him wondering about the connection of that particular image with Arthurian lore.<

br />

Artorius, the Dux Bellorum who commanded the Sarmatian cataphracti...

Ancelotis said silently, When Artorius was still a young lad, not yet turned seventeen, but already showing signs of promise as a shrewd and successful war leader, he persuaded the Sarmatians of Gododdin to finally give up their pagan gods and follow Christian ways. They began referring to him as the man who pulled the Sarmatian sword from its sacred stone, a true war leader who replaced their centuries-old tribal icon with a new god and new ways of worshiping. They also say he's the only mortal man ever born worthy to drain their sacred cup of heaven, like enough to Christ's grail, it wasn't so difficult for them to switch their allegiance to Artorius' new god. It didn't hurt, of course, that Uthyr Pendragon was one of their own...

Stirling blinked. No wonder Artorius looked more Eurasian than Briton.

Oh, aye, Ancelotis agreed, he's one of them, right enough, and they know it. They would dare things in battle under Artorius' direction they wouldn't even consider, when my brother, King Lot, was giving the orders. These men will follow Artorius anywhere and gladly die for him, if they must. In their eyes, he is more of a king than I will ever be, more than the Dux Bellorum of the Britons, far more than just their commander. They have given him their sacred souls for safekeeping. And he has never betrayed that trust.

Nor would he ever betray it, Stirling realized numbly. Arthur, tribal "king" of the Sarmatian cataphracti of Britain... The far-reaching implications shook him, even while explaining the astonishing persistence of the sword-in-the-stone tale.

He shook himself slightly, focusing his attention on the men themselves. The cavalrymen wore an assortment of gear as widely varied as their genetic heritages. Most sported iron helmets, either of Roman design—looking something like a metallic baseball cap worn backwards, with protective metal cheekpieces—or a Celtic adaptation with conical iron points jutting upward and to the rear like metallic goats' horns. Many of the helmets, whatever style they might be, sported masses of feathers designed to make the wearer seem taller and more fierce.

All the men of the cataphracti wore close-fitting woolen trousers in wild checks and plaids, bloused and tied at the ankles over leather boots. Some wore wild-animal skins, others linen or leather tunics beneath Roman scale or ring-mail armor which glittered dangerously in the early sunlight, but most of them wore the scale armor that was a hallmark of Sarmatian heavy cavalry and had been for hundreds of years, going back several centuries before Christ even.

They were armed with a bewildering array of Saxon war axes, single- and triple-bladed spears with typically Celtic ironwork points, which were long and heavy, with concave edges. He also saw heavy Roman cavalry broadswords plus lances and javelins, even short Sarmatian bows and quivers full of bristling arrows. Iron-studded wooden shields—long, slightly dished ovals—were painted in bright colors, with a confusing mix of Christian and pagan symbols. Many of the weapons were heavily decorated with silver inlay, particularly sword and dagger hilts. The better a man's armor, he noted with a narrow-eyed glance, the more ornate his weaponry; but all of it was lethally functional. No ceremonial nonsense anywhere in sight.

Most of the horses wore at least minimally armored leather harnesses with circular metal bosses, which were spaced at regular intervals, wrought of iron and bronze. A fair number wore heavy coats of the same Sarmatian scale armor as their riders. Saddles were cinched tightly over fringed saddlecloths, many of them wildly patterned to match their owners' trousers. The saddles themselves were oddly horned affairs with four jutting projections that cradled a man's leg front and back. Weapons, water bags, and other equipment hung from leather cords slung around the saddles' four horns.

The detail that caught his eye almost instantly, however, was the presence of solid iron stirrups. Surprise caught him again—and Ancelotis chuckled once more. A grand invention of our Sarmatian cataphracti, eh? The Saxons were as shocked as you to see stirrups the first time we rode them down. He added with justifiable pride—and a dark sense of wasted lives and effort—Had the Roman legionary commanders understood cavalry as well as we Britons, they might not have lost an empire.

Stirling couldn't argue that. Roman generals had been notorious in their poor understanding of the proper uses of cavalry. Clearly, Artorius and Ancelotis and their Sarmatians had not made the same error.

Stirling was distracted by the sight of the beautiful copper-haired girl with the fur-lined cloak who had paid him a secret visit. She had already mounted a smaller horse, more suited to her petite frame than the massive horses of the armored cataphracti. Palfrey, they would call the smaller riding animal in later centuries. She sat easily in the saddle, however, clearly accustomed to riding astride. She looked very nearly as competent in the saddle as the armed warriors of their escort and she'd slung a smaller version of a war sword at her hip.

"Ganhumara." Artorius gave a curt nod to the lady as he accepted his own armor and helm, donning them with help from a standard bearer. Artorius' golden standard had clearly been modeled after the legionary eagles. For a legionary soldier, the eagle had been his personal "household" god and protector. The dragon standard was a brilliant ploy, echoing centuries of Roman military symbology, yet portraying a uniquely Briton symbol of nationhood.

A second rider carried another dragon standard, this one with distinctly Sarmatian alterations. The head of this second dragon was gold, as well, with silver throat and fangs. And fastened to it, exactly like those on the Sarmatian spears, was a blood-red dragon, its cloth body rippling like an angry, living beast in the stiff wind. The streamers of its tail would be visible even in the midst of battle, Stirling realized, providing a rallying point even easier to spot than the solid gold shape of the other standard.

Servants assisted Artorius into a Roman officer's burnished cuirass, ornate enough to have been worn by a victorious general during a triumph. Artorius settled onto his head a Celtic-style iron helm, covered with gold leaf and topped by a rampant dragon, clearly a Sarmatian symbol. He belted on sword and dagger and slung a crimson cloak of thick wool around his shoulders, pinning it with a heavy gold cloak pin of a style variously attributed to Celts and Vikings, then he vaulted easily into the saddle despite the weight of his armor.

His mount, a gleaming white stallion as big as a house, arched its neck and blew impatiently, pawing at the cold ground and rolling a wild, dark eye. Artorius checked the massive animal with a sharp word and a tightening of reins before accepting a long spear from the standard bearer. The bearer then mounted and took up position on Artorius' left flank, his gold-dragon standard glinting with burnished highlights in the cold sunlight.

Another servant brought up Ancelotis' armor, while others emerged from the fortress, carrying what must have been Artorius'—or Ancelotis'—personal baggage. Or maybe Ganhumara's. The heavy satchels and cases were strapped to pack animals while Stirling wrestled with unfamiliar fittings on Ancelotis' armor. The Briton king's personal armor was also of Roman design, nearly as ornate as Artorius', and must have been a well-preserved century old, at the very minimum. Unless there were still trade routes open to the Continent? Stirling didn't know enough to hazard a guess and Ancelotis wasn't saying.

Ancelotis' helm, unlike Artorius', followed the design of very late Roman cavalry. Burnished gold over the strong iron beneath, it formed a metal mask that completely enclosed his head, like an iron skullcap with cheekpieces that hinged around to cradle cheek and chin in metal. A thick blade of gold-covered iron projected above his brows, protecting eyes and to some extent nose from a glancing sword blow. He could smell dried sweat inside it, from many previous wearings as he settled it over his head.

His valet handed Stirling a thick woolen cloak of his own, dyed a brilliant scarlet-and-blue plaid, held closed across one shoulder with another circular cloak pin. His was decorated with chased dragon patterns and apparently made of solid silver. The artistry he'd already glimpsed in clothing and metalwork surprised Stirling—he'd expected su

ch artifacts to be far more primitive. A modern man's prejudice, he realized, founded on nothing more than arrogance, when this culture was a direct heir of Roman civilization.

Morgana and Medraut appeared from the fortress a moment later, the latter carrying a heavy satchel of ornately decorated leather which he strapped to Morgana's saddle. Servants brought other satchels and bags, which they tied to pack animals. Morgana floated effortlessly into the saddle, despite the weight of a heavy, fur-lined cloak similar to Ganhumara's. Stirling gulped, realizing he would have to get onto his own horse before he could figure out how to ride it, and blessed the unknown Sarmatian who'd brought cavalry stirrups to the Scottish border country. Another woman Stirling vaguely recalled seeing from the night of his collapse appeared, blonde hair plaited neatly down her back, slim and beautiful in white woolen robes and a heavy cloak of dark fur. She, too, had a heavy satchel, which she strapped to her saddle.

The Dux Bellorum watched her mount, then spoke to Ganhumara, his voice nearly as cold as the wind. "We have a hard ride ahead, to reach Caerleul before Cutha and Creoda. We will ride by forced march, to the detriment of your comfort. I did warn you," he added. "It's no pleasure jaunt we're about, but preparation for war."

She lifted a shapely copper brow and said coolly, "I am as fine a rider as you, husband, and a battle queen in my own right, if not so skilled with a sword."

Steel-cold eyes glinted beneath glowering brows. "It is not your skill with saddle or sword which concerns me," Artorius growled. "Your stamina is not my equal, wife, and after the delay we've already had, to treat Ancelotis' illness, I will slow our pace for nothing and no one. If you cannot keep up, I will leave armsmen as an escort and ride on without you. Ancelotis, we dare delay no longer."

The Complete Phule’s Company Boxed Set

The Complete Phule’s Company Boxed Set The Adventures of Duncan & Mallory: The Beginning

The Adventures of Duncan & Mallory: The Beginning Myth Conceptions

Myth Conceptions Sween Myth-tery of Life m-10

Sween Myth-tery of Life m-10 Hit Or Myth m-4

Hit Or Myth m-4 MA08 Myth-Nomers and Im-Pervections

MA08 Myth-Nomers and Im-Pervections Catwoman - Tiger Hunt

Catwoman - Tiger Hunt myth-taken identity m-14

myth-taken identity m-14 MA03 Myth Directions

MA03 Myth Directions MA07 MYTH Inc Link

MA07 MYTH Inc Link Dragons Luck

Dragons Luck MYTH-Interpretations: The Worlds of Robert Asprin

MYTH-Interpretations: The Worlds of Robert Asprin MA10 Sweet Myth-tery of Life

MA10 Sweet Myth-tery of Life No Phule Like an Old Phule

No Phule Like an Old Phule Phule's Errand pc-6

Phule's Errand pc-6 Myth-ion Improbable

Myth-ion Improbable MA11-12 Myth-ion Improbable Something Myth-Inc

MA11-12 Myth-ion Improbable Something Myth-Inc Sweet Myth-tery of Life

Sweet Myth-tery of Life MA02 Myth Conceptions

MA02 Myth Conceptions Myth-Fortunes m-19

Myth-Fortunes m-19 Myth Alliances m-14

Myth Alliances m-14 Wagers of Sin

Wagers of Sin Myth Directions

Myth Directions The Bug Wars

The Bug Wars Ripping Time

Ripping Time MA09 Myth Inc in Action

MA09 Myth Inc in Action MA06 Little Myth Marker

MA06 Little Myth Marker Phules Paradise

Phules Paradise Myth-Nomers & Im-Pervections

Myth-Nomers & Im-Pervections Wartorn: Resurrection w-1

Wartorn: Resurrection w-1 Phule's Errand

Phule's Errand Time Scout

Time Scout Tambu

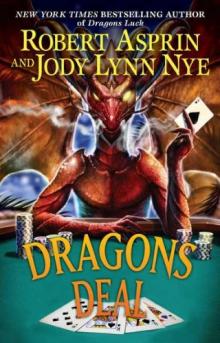

Tambu Dragons Deal

Dragons Deal MYTH-Taken Identity

MYTH-Taken Identity Myth-Told Tales

Myth-Told Tales Dragons deal gm-3

Dragons deal gm-3 Myth-Nomers and Im-Pervections m-8

Myth-Nomers and Im-Pervections m-8 Little Myth Marker

Little Myth Marker The Adventures of Duncan & Mallory

The Adventures of Duncan & Mallory Dragons Wild

Dragons Wild Myth-ion Improbable m-11

Myth-ion Improbable m-11 Myth-Ing Persons m-5

Myth-Ing Persons m-5 Dragons Luck gm-2

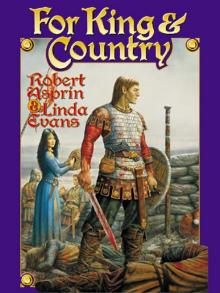

Dragons Luck gm-2 For King and Country

For King and Country The Blood of Ten Chiefs

The Blood of Ten Chiefs E.Godz

E.Godz MYTH CONCEPTIONS m-2

MYTH CONCEPTIONS m-2 Myth Directions m-3

Myth Directions m-3 Class Dis-M.Y.T.H.ed

Class Dis-M.Y.T.H.ed A Phule and His Money

A Phule and His Money Aftermath tw-10

Aftermath tw-10 The House That Jack Built

The House That Jack Built Stealers' Sky tw-12

Stealers' Sky tw-12 Uneasy Alliances tw-11

Uneasy Alliances tw-11 Wages of Sin

Wages of Sin M.Y.T.H. Inc In Action m-9

M.Y.T.H. Inc In Action m-9 Another Fine Myth

Another Fine Myth Myth Alliances

Myth Alliances The Cold Cash War

The Cold Cash War M.Y.T.H. Inc. Link m-7

M.Y.T.H. Inc. Link m-7 Wartorn Obliteration w-2

Wartorn Obliteration w-2 License Invoked

License Invoked Myth-Told Tales m-13

Myth-Told Tales m-13 Hit Or Myth

Hit Or Myth Myth-Ing Persons

Myth-Ing Persons Phule's Company

Phule's Company MA04 Hit or Myth

MA04 Hit or Myth MA05 Myth-ing Persons

MA05 Myth-ing Persons Something MYTH Inc m-12

Something MYTH Inc m-12 Mirror Friend, Mirror Foe

Mirror Friend, Mirror Foe Dragons Wild gm-1

Dragons Wild gm-1 M.Y.T.H. Inc in Action

M.Y.T.H. Inc in Action Class Dis-Mythed m-16

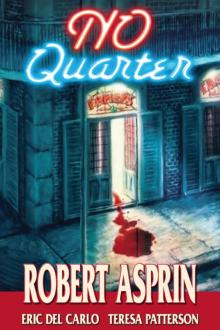

Class Dis-Mythed m-16 NO Quarter

NO Quarter