- Home

- Robert Asprin

For King and Country Page 11

For King and Country Read online

Page 11

Before tying off the trouser cuffs, Stirling reached for a close-fitting linen tunic dyed a rich blue, over which went a long woolen tunic, in bright shades of reds, oranges, greens, and blues, the garish precursors of Scots tartan. The effect of plaid tunic and checked trousers offended Stirling's admittedly Philistine aesthetic sense. The thought prompted a grin, however, as mercifully there was no mirror in evidence to check the gaudy result. The quality of the cloth was surprisingly high, considering the century of invasions Briton kingdoms had endured following the collapse of Roman government. He wondered what further surprises the sixth century would hold?

Light footsteps caught his attention as he picked up thick leather boots. A tap sounded at his door, which opened on silent leather hinges. Stirling wasn't sure whom he expected, but it wasn't the startlingly beautiful girl who slipped inside, at first glance no more than half grown, but at second glance perhaps as much as a very young seventeen or eighteen. Eyes the color of deep blue ice gazed at him in wide concern. Copper hair streamed over one shoulder in a cascade that stopped his breath.

Her gown, of a far more attractive style than he'd expected, clinging delightfully to her more than delightful curves, was cinched around an impossibly tiny waist by a belt apparently made from solid gold links. The woolen gown had been dyed a blue as striking as her eyes. Jewels glittered at her wrists and ears. A heavy woolen cloak, startling in shades of crimson-and-green plaid and lined with soft white fur, hung from her shoulders, held closed across her breasts by a jeweled chain.

"You're awake at last!" she breathed.

Belatedly, he noticed the golden circlet at her throat. Torque of royalty... Was this woman his—or rather, Ancelotis'—wife? Ancelotis' reply growled through his confusion. She's no wife of mine, a fact she forgets far too frequently. Her identity, reaching him from Ancelotis' memories, burst into Stirling's awareness with cold horror. Ohshit, ohshit, ohshit... He stood up hastily, which was a mistake, given his poor coordination. He stumbled off balance and the girl gasped, darting forward to steady him.

"I'm no child!" he snapped, pulling free and wondering for a bad moment if he'd spoken in Brythonic Welsh or English. She froze, eyes wide. The beginnings of fear—and anger—began to spark in those lovely pale eyes.

While Stirling scrubbed at his face, trying to dredge up some kind of response, Ancelotis simply muttered, "Forgive my short temper, it's that damned potion of Morgana's."

For a long, hazardous moment, she said nothing at all; then the danger passed and she relaxed, although she remained standing far too close for his peace of mind. "Aye," she nodded. "Belike. Druids' potions have left me dizzy a time or two."

He glanced curiously into her eyes, wondering about that. No sense in asking, however; that could be even more disastrous than snapping at her had been. "I am all right, truly," he tried to reassure her.

"What happened?"

He shook his head, neither of them able to come up with an explanation that sounded even remotely plausible. "It doesn't matter. I'm fine now."

Her glance remained wary, but she didn't press the issue. Just how much did a Briton woman argue with her menfolk? Ancelotis didn't answer him, instead speaking with a firmness that bordered on the grim.

"Thank you for making certain I'm all right, but you had better go."

She glared at the door with a flash of defiance, then her shoulders drooped, as though her cloak—or some other burden—were far too heavy. "Aye. It wouldn't do to stir trouble just now. The council met while you slept," she added, eyes flashing with some strong emotion Stirling couldn't interpret. "Summoned by Artorius from the capital."

"And did the councillors take a vote while I slept?" he asked, voice on edge for a reason Stirling didn't quite understand.

Her ice-pale eyes glinted. "They did. You're wanted in the great hall."

"In that case," Ancelotis said coolly, "you had best not be here when they come to fetch me."

Her eyes flashed, rebellious again, but she subsided without further verbal protest. She did take one worried step forward—Stirling was pretty sure it was worry that prompted it—and checked abruptly at some tiny signal he hadn't realized he'd telegraphed until too late. She caught back a sob—of rage or frustration or grief, he had no idea. Then she whirled aside and snatched at the door, peering carefully into the corridor before slipping away with a rustle of woolen skirts. Stirling discovered an unmanly tremor in his knees and an even more disturbing response at his groin.

This was worse than riot duty in Clonard.

Ancelotis muttered, A man may leave a city of his free will, if life there displeases him, but a woman like Ganhumara will plague a man to the grave, stirring trouble wherever she sets foot. And she but a girl scarce grown to womanhood.

That, Stirling thought grimly, was doubtless the best reason for avoiding female entanglements he'd ever heard. He sat back down to tug on his boots, scrubbed his face for a long moment, and thought seriously of finding a very deep and icy lake to jump into. He was still wrapping ankle laces around his trouser cuffs when the door opened again, the knock so peremptory as to be nonexistent.

"Ancelotis! You're looking much better!"

Stirling found himself facing a man in his mid-thirties, perhaps a little older. His face had been deeply weathered by sun and worry and the harshness of battle. There was an odd, out-of-place look about his features, better suited to the wilds of Persia than the Lowlands of Scotland. He wasn't tall, but only a fool would've made the mistake of calling him a small man. Stocky, athletic under a tunic and loose trousers of cut and quality comparable to the ones Stirling wore, his hands were scarred and calloused. His nose had been broken at least once and his stance communicated instant readiness to fight. It was not belligerence. Stirling had seen that look of hair-trigger readiness before, in the faces of soldiers in a combat zone. This was a man accustomed to war. And command. And victory.

A golden torque, much smaller than the one Stirling wore, narrower even than the copper-haired girl's, glittered at the man's throat. High rank, then, but not quite royalty. A red dragon, hand-embroidered by some skilled needlewoman, blazed scarlet on the breast of his tunic, giving Stirling the final clue he needed, confirmed by Ancelotis.

Artorius.

Dux Bellorum of the People of the Red Dragon.

He didn't even know how to address this man. The word "sire" froze in the back of his throat. Artorius wasn't a king. That didn't stop Stirling from thinking dazedly, My God, it's King Arthur in person... .

Artorius was staring at him rather oddly. "You are all right, Ancelotis?"

He managed a nod. "Aye. It's that blasted potion." He winced at using the same lame excuse, but Artorius merely grunted.

"You'll need a clear head by week's end, man. The council's voted. I sent for them the moment you collapsed. They're in full agreement and Queen Morgana gives you her full backing."

Stirling had not the faintest idea what Artorius was talking about, but his host's reaction gave him an unpleasant clue. Ancelotis blanched, groping for the bed and sinking onto it before his knees gave way.

"She's refused it, hasn't she?"

"You cannot be surprised by that."

Ancelotis ran a distracted hand through his hair, a movement that startled Trevor Stirling, who still wasn't accustomed to having his body respond to commands he hadn't given. "No," Ancelotis agreed with a sigh. "It doesn't surprise me. If anything, I respect her the more for it. They've given it to me, have they? Until Gwalchmai is of age?"

"They have. I fear the formal ceremony must be kept far briefer than you might wish."

Ancelotis snorted. "I would wish for none at all to be needed. It was never my intent to rule Gododdin—or anything else, save my warhorse and a cavalry unit or two. That was Lot's desire, never my own."

Artorius' weathered face betrayed the depth of his concern in a whole series of deepened gullies through cheeks and brow. "This cannot be easy for you, old friend, nor is what I must

ask now. I came to Caer-Iudeu because I had great need of both you and your brother in this matter of the Saxon challenge. This trouble has not diminished simply because the mantle of kingship has fallen onto your shoulders. I must ask it, Ancelotis, for the good of Britain. Don't return to Trapain Law yet."

"But—"

"Gododdin may be as far from the troubles of the south as it is possible to go in Briton territory, but if we allow Cutha and his machinations free reign while you look to Gododdin's internal affairs, you will wake one morning all too soon to find Cutha and his ilk massing on your border, not Glastenning's. Covianna Nim brought the demands from Cutha of Sussex and his puppet Creoda of Wessex, at the request of the abbot of Glastenning Tor. They are pushing, Ancelotis, and pushing hard. Glastenning is not yet theirs, yet already their eyes have turned north to Rheged—and if Rheged falls, my friend, there is no kingdom of the north that will be able to stand against them."

Ancelotis scrubbed his brow wearily with both hands, listening and cursing under his breath at every new piece of unpleasant news. "The kings of Dumnonia and Glastenning have asked your help?"

"They have. There must be a council of the kings of the north, to answer this Saxon challenge, to act in support of the kings of the south. Come with me to Caerleul, Ancelotis. Morgana rides with us to speak for Galwyddel and Ynys Manaw."

"And Ganhumara will speak for Caer-Guendoleu?"

Irritation flickered through Artorius' eyes. "She will. Would that God had granted her father another few years of life."

"And you wonder why I have never married?"

"No longer," Artorius shot back dryly. "Do yourself a favor, old friend, and marry a cowherd's daughter—queens of the blood have too much ambition and pride to make a man happy."

He held the Dux Bellorum's gaze for a long moment. "I grieve to hear you say it. Very well, Artorius, I will ride to Caerleul and speak for Gododdin in council. Does King Aelle of Sussex send his youngest son to us alone? Or does Cutha travel with company as pleasant and reasonable as that vile and odious mercenary he calls father? You had no real opportunity to give us details yesterday, with the fighting and Lot's death."

"No, Cutha of Sussex does not ride alone. God help us all, he's bringing Creoda with him. And it's Prince Creoda who's demanding a place in Rheged's council. You know only too well what that means."

Ancelotis swore with impressive Brythonic creativity.

Artorius grunted agreement. "King Aelle sits on his self-crowned throne and laughs at fools like Creoda, bootlicking dogs, he and his father both, styling themselves Saxons to hold onto lands they should have fought to protect. Gewisse, their own allies call them, and with good reason. His scheming grows ever bolder, Ancelotis, which is why I must speak to the kings of the north in council, without delay. Damn Creoda and his fool of a father, Cerdic, for selling their Saxon paymasters the rights they hold as Briton kings, to join our privy councils. 'They only wish to parlay,' was the message brought north by Covianna Nim."

Artorius growled, striking his open palm with a fist. "May the gods of our ancestors help us, for it is better—at least for now—that we talk when they offer it, than bleed for lack of trying." Artorius paced the room, an enraged dragon caged in far too small a space. "King Aelle is a crafty bastard, I'll give him that much, and Cutha is a right and proper twig off his branch. They supported Cerdic's bid for power and won him the thrones of Caer-Guinntguic and Caer-Celemion and Ynys Weith, and now they've turned that gain into a Saxon-controlled fiefdom with a stinking Saxon name. Wessex!"

Artorius spat disgustedly. "West Sussex, there's what that name really means, for you, and that name is our greatest danger, Ancelotis. Briton kings toppled by Briton traitors anxious for a taste of power for themselves and their by-blows of whores, too blinded by greed to see the price their Saxon masters will demand. Five years!" he snarled. "Five years, Creoda and his bastard of a father have strutted themselves under Saxon patronage, demanding treaties of alliance to secure guarantees they won't attack, and what have the kings of the south done about it? Nothing! While Aelle the mercenary grows fat and rich on land stolen from Briton widows and orphaned babes! God curse that fool, Vortigern, for hiring Saxon foederati fifty years ago!"

"Yes," Ancelotis agreed darkly, "Vortigern was as big a fool as Cerdic and Creoda, and the damned Saxons have been arriving by the shipload ever since." As Ancelotis spoke, Stirling was frantically casting back through his history lessons, trying to recall when the Kingdom of Wessex had been established, somewhere about the year 495, he thought. Which meant he'd landed more or less precisely on target. This ought to be the year of the historic battle of Mons Badonicus, Artorius' wildly famous twelfth battle.

Well, some scholars thought Mount Badon had been fought in the year a.d. 500, anyway. Others put it as many as twenty, thirty years later, and who in hell was to know, at this late remove, which piecemeal shattered records might hold the slightly larger grains of truth, never mind anything approaching genuine accuracy? All that could be said with certainty was that Artorius' victory at Badon Hill had driven the Saxons to their knees for nearly forty years, uniting Britons from the Scottish border to the southern tip of Cornwall.

Ensuring Artorius' defeat at Mount Badon could do a lot of damage. Enough to destroy a world. His world, Stirling's twenty-first-century one, with its billions of ordinary, innocent men, women, and kids, families watching the telly and taking a tea-time stroll through a world they naively believed to be safe.

The trouble was, no one, not even the scholars and archaeologists, knew where "Badon Hill" was supposed to be, which made Stirling's job trying to protect Artorius from being killed there a bit trickier. And Artorius was still pacing.

"We daren't show weakness before Cutha, old friend," he growled, pinning Ancelotis' eyes with a cold, hard look of anger. "Creoda may be a fool, but Cutha is another breed altogether. Aelle sends his son to us as spy, more than emissary, with Prince Creoda as means to a Saxon end." Steel-grey eyes glinted. "He'll challenge us to a test of arms, I have no doubt of that. Exhibition games with a darker purpose. Your brother's death will at least give us an excuse to stall them for a bit. We can declare traditional funerary games in his honor, even at Caerleul, to pay respect. King Meirchion Gul of Rheged will not stint Lot's memory, for Queen Thaney's sake, if for no other reason."

Ancelotis winced inwardly. "Thaney, surely, has not forgiven her father?"

Artorius grinned. "You know your niece better than anyone, Ancelotis. To my somewhat shaky knowledge, she has not forgotten any more than she's forgiven, but she remembers all too clearly the debt she owes you and Morgana, for helping her escape Lot's anger. Besides, the matter of paying proper tribute to her father's memory touches her honor as princess of Gododdin and queen of Rheged. And Thaney," Artorius chuckled a trifle grimly, "is a creature of honor, which you know only too well."

Ancelotis snorted. "That she is. All right, I won't worry about Thaney."

"Good. The funerary games will give us both the delaying tactic and excuse we'll need to gather all the kings of the north for council. It will also give us the opportunity to meet the challenge Cutha will inevitably deliver in the manner which best suits us. Fortunately," a nasty smile flashed into existence, "the Saxons are infantrymen. They ride horses only to reach the battlefield. They cannot match our heavy Roman cavalry, eh?"

Stirling bit back sudden panic.

He'd never been on a horse in his life.

Artorius frowned. "You're still pale, old friend. Would to God you could rest and recover your strength, but there simply isn't time. It's a long ride to Caerleul, if we hope to arrive before Cutha and his gewissan fool, Creoda. Damn, but it's a hellishly bad time for Lot to've gone riding after Pictish raiders! And the women, bless their good intentions, will slow us even further."

"Women?" Stirling blurted before Ancelotis could curb his tongue.

"Aye," Artorius nodded glumly. "Covianna Nim, who brought the news and insisted on riding wit

h me to fetch Lot. Ganhumara, who would not hear of Covianna riding alone with me and demanded the right to accompany us. It's no fit time for Ganhumara to set foot outside the garrison at Caerleul, rail as she will about her status as battle queen in her own right. But she will throw her royal blood into the argument and, as queen of Guendoleu, I cannot ignore her demands, as I might a lesser wife's."

Artorius sighed, with the look of a man hard pressed to maintain peace on the home front, even as Stirling tried to take in the notion of that slender girl leading warriors into battle.

"And Morgana, of course," Artorius added, "will be riding with us. She must give her vote as queen of Galwyddel and Ynys Manaw." Stirling nodded, worried that the real delay wouldn't be the women and not daring to admit it out loud. Artorius rested a hand on his shoulder. "Can you ride, Ancelotis?"

"I'll manage," Stirling growled, tugging uneasily at the gold torque around his neck. It wouldn't do for not-yet-crowned King Ancelotis to develop a sudden nervousness of travel by horseback. He sighed. He'd have to work doubly hard to make sure King Ancelotis didn't sprawl onto his royal backside in the dust, trying.

* * *

The ceremony was a brief one, startling in its sixth-century simplicity. It took place in a large room that clearly served as the principium, or headquarters building, of the fortress atop Stirling Cliff. There were no murals, here, just cracked plaster over well-shaped stones roughly the size of bricks. The floors were simple stone flagging, once again joined with skill. Oil lamps burned bright, hanging from the soot-streaked ceiling, resting in iron lamp stands along the walls, cheering up the heartlessly plain room with flickers of golden light across ceiling and walls. The room was big enough to have served as officers' mess, war room, and dance hall, with large tables of rough-hewn wood and enough chairs to accommodate a meeting of a hundred, without any difficulty.

And there were enough men in the room to have filled every one of those chairs, all of them waiting for his arrival. Ancelotis was greeted informally by a rousing cheer from the men of his command and formally by one group of twelve, all of them older men with grey in their hair, who served Gododdin as a senior council of advisors. Among them was a Christian priest, distinguishable by his long, monkish robes, which were nevertheless of good quality, and by the cross he wore, an ornate and beautiful Celtic cross of exquisite workmanship. He was holding a gold torque that Ancelotis, at least, recognized as having been his older brother's.

The Complete Phule’s Company Boxed Set

The Complete Phule’s Company Boxed Set The Adventures of Duncan & Mallory: The Beginning

The Adventures of Duncan & Mallory: The Beginning Myth Conceptions

Myth Conceptions Sween Myth-tery of Life m-10

Sween Myth-tery of Life m-10 Hit Or Myth m-4

Hit Or Myth m-4 MA08 Myth-Nomers and Im-Pervections

MA08 Myth-Nomers and Im-Pervections Catwoman - Tiger Hunt

Catwoman - Tiger Hunt myth-taken identity m-14

myth-taken identity m-14 MA03 Myth Directions

MA03 Myth Directions MA07 MYTH Inc Link

MA07 MYTH Inc Link Dragons Luck

Dragons Luck MYTH-Interpretations: The Worlds of Robert Asprin

MYTH-Interpretations: The Worlds of Robert Asprin MA10 Sweet Myth-tery of Life

MA10 Sweet Myth-tery of Life No Phule Like an Old Phule

No Phule Like an Old Phule Phule's Errand pc-6

Phule's Errand pc-6 Myth-ion Improbable

Myth-ion Improbable MA11-12 Myth-ion Improbable Something Myth-Inc

MA11-12 Myth-ion Improbable Something Myth-Inc Sweet Myth-tery of Life

Sweet Myth-tery of Life MA02 Myth Conceptions

MA02 Myth Conceptions Myth-Fortunes m-19

Myth-Fortunes m-19 Myth Alliances m-14

Myth Alliances m-14 Wagers of Sin

Wagers of Sin Myth Directions

Myth Directions The Bug Wars

The Bug Wars Ripping Time

Ripping Time MA09 Myth Inc in Action

MA09 Myth Inc in Action MA06 Little Myth Marker

MA06 Little Myth Marker Phules Paradise

Phules Paradise Myth-Nomers & Im-Pervections

Myth-Nomers & Im-Pervections Wartorn: Resurrection w-1

Wartorn: Resurrection w-1 Phule's Errand

Phule's Errand Time Scout

Time Scout Tambu

Tambu Dragons Deal

Dragons Deal MYTH-Taken Identity

MYTH-Taken Identity Myth-Told Tales

Myth-Told Tales Dragons deal gm-3

Dragons deal gm-3 Myth-Nomers and Im-Pervections m-8

Myth-Nomers and Im-Pervections m-8 Little Myth Marker

Little Myth Marker The Adventures of Duncan & Mallory

The Adventures of Duncan & Mallory Dragons Wild

Dragons Wild Myth-ion Improbable m-11

Myth-ion Improbable m-11 Myth-Ing Persons m-5

Myth-Ing Persons m-5 Dragons Luck gm-2

Dragons Luck gm-2 For King and Country

For King and Country The Blood of Ten Chiefs

The Blood of Ten Chiefs E.Godz

E.Godz MYTH CONCEPTIONS m-2

MYTH CONCEPTIONS m-2 Myth Directions m-3

Myth Directions m-3 Class Dis-M.Y.T.H.ed

Class Dis-M.Y.T.H.ed A Phule and His Money

A Phule and His Money Aftermath tw-10

Aftermath tw-10 The House That Jack Built

The House That Jack Built Stealers' Sky tw-12

Stealers' Sky tw-12 Uneasy Alliances tw-11

Uneasy Alliances tw-11 Wages of Sin

Wages of Sin M.Y.T.H. Inc In Action m-9

M.Y.T.H. Inc In Action m-9 Another Fine Myth

Another Fine Myth Myth Alliances

Myth Alliances The Cold Cash War

The Cold Cash War M.Y.T.H. Inc. Link m-7

M.Y.T.H. Inc. Link m-7 Wartorn Obliteration w-2

Wartorn Obliteration w-2 License Invoked

License Invoked Myth-Told Tales m-13

Myth-Told Tales m-13 Hit Or Myth

Hit Or Myth Myth-Ing Persons

Myth-Ing Persons Phule's Company

Phule's Company MA04 Hit or Myth

MA04 Hit or Myth MA05 Myth-ing Persons

MA05 Myth-ing Persons Something MYTH Inc m-12

Something MYTH Inc m-12 Mirror Friend, Mirror Foe

Mirror Friend, Mirror Foe Dragons Wild gm-1

Dragons Wild gm-1 M.Y.T.H. Inc in Action

M.Y.T.H. Inc in Action Class Dis-Mythed m-16

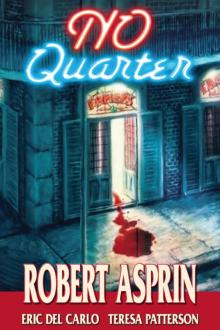

Class Dis-Mythed m-16 NO Quarter

NO Quarter